Natural or unnatural?

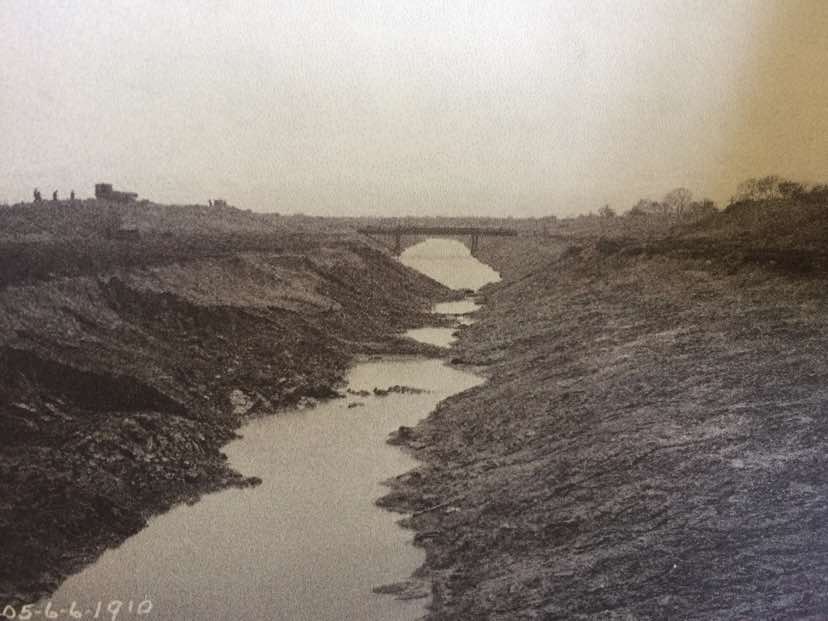

The North Shore Channel was constructed in 1907–10 as part of the Chicago region's sewage and water management system. Most of the channel followed the path of an earlier ditch that drained marshy land once found here.

In June 1910, when the photograph below was taken, the channel had been excavated, but the soft clay channel banks were failing and slipping into the excavation. You're now standing on the bridge you can see in the distance in the photograph.

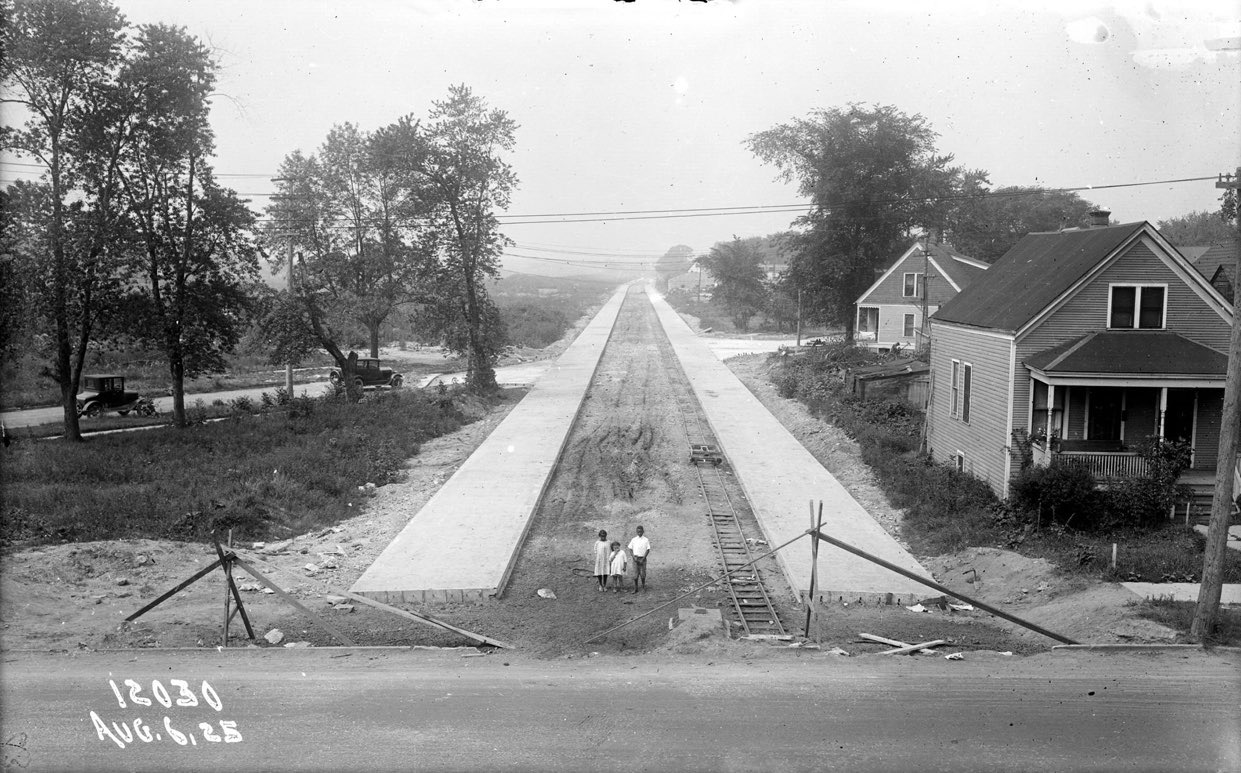

Looking south along McCormick Boulevard from Green Bay Road, 1925. Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD)

A pumping station located under the Sheridan Road Bridge in Wilmette lifted clean water from Lake Michigan into the channel, causing it to flow south into the polluted North Branch of the Chicago River. Along the way, sewers in Wilmette, Evanston, and Skokie discharged sewage into the channel. A major engineering project had already reversed the flow of the Chicago River to keep its polluted water out of Lake Michigan. Water from the North Shore Channel joined the Chicago River and flowed on south into the Des Plaines, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers, and eventually the Gulf of Mexico.

Is this water dangerous?

The North Shore Channel no longer receives raw sewage. Since 1928, sewage has been collected and conveyed through a system of intercepting sewers that lie beneath McCormick Boulevard, which flows south to the O'Brien Water Reclamation Plant at Howard and McCormick.

Now, the channel water is normally safe for boating, and during the warmer months, you are likely to see rowers here. But during heavy storms, the combined sewers in Wilmette, Evanston and Skokie sometimes overflow, and a mixture of sewage and stormwater is released into the channel.

This happens much less often than it used to thanks to TARP, the Tunnel and Reservoir Project, or Deep Tunnel. There are TARP drop shafts on both sides of the channel north and south of here. After a big storm, excess combined sewer overflow is held in the deep tunnel before it is conveyed to the Stickney Water Reclamation Plant for complete reclamation.

You can get alerts about CSOs, combined sewage overflow events, from Friends of the Chicago River @chicagoriver

Friends of the Chicago River planting lizard’s tail along the water’s edge

In this 1925 photograph showing construction of McCormick Boulevard, the future Ladd Arboretum is on the left; Kingsley School would later replace the house on the right. Source: Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD)

Drop shaft near Green Bay Road

Why is the water sometimes green?

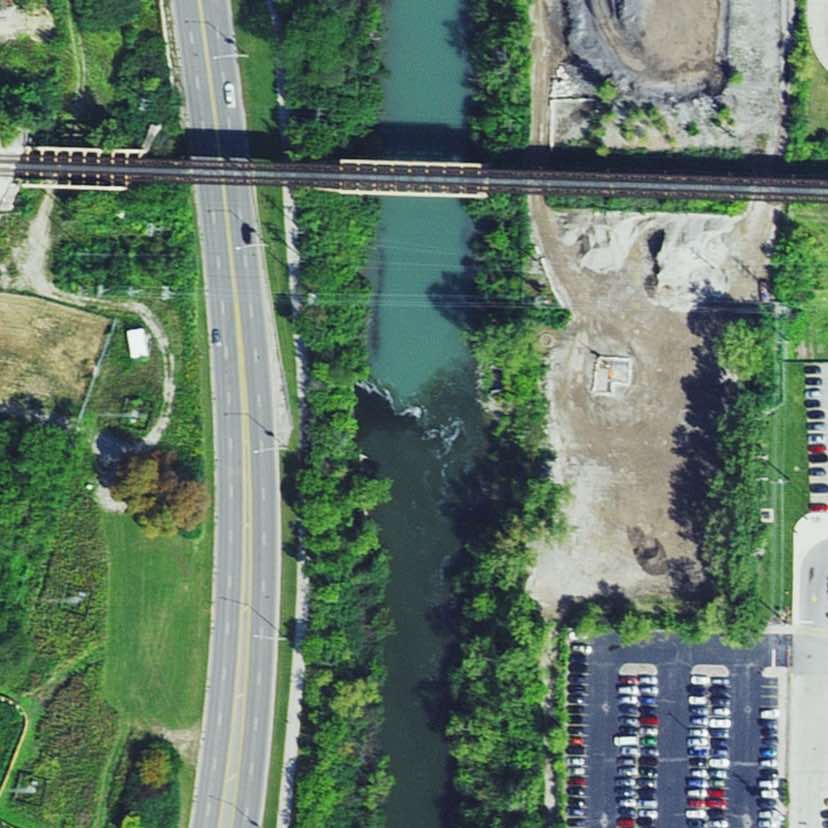

Water color change at the O’Brien Water Reclamation Plant — Courtesy Apple Maps satellite view

See the difference in color of the North Shore Channel water in this satellite image of the area near Oakton and McCormick Boulevard? This is where the O’Brien Water Reclamation Plant is located.

Water is released from the Water Reclamation Plant through an outfall between Oakton and Howard Street and from there flows south. This water has a very low concentration of suspended solids—tiny particles of things like clay, sand, or decaying leaves. On this image, this clean water looks black because there are few solids in the water to reflect light.

The water north of the outfall (including the section of the channel that passes through Evanston) is stagnant or slow-flowing. The native soft clay, sometimes disturbed by common carp, is held in the water by colloidal suspension. These suspended solids reflect the color of the sky and surrounding trees and often make the water here look milky or blue-green.

Learn more from these sources

Libby Hill (2nd ed. 2019) The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History

Richard Lanyon (2016) Draining Chicago: The Early City and the North Area

The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD, formerly Sanitary District of Chicago) is the source of historic images. MWRD owns the land along the channel and leases this section to the City of Evanston.

City of Evanston North Shore Channel Habitat Project evanstonhabitat.org

Legacy

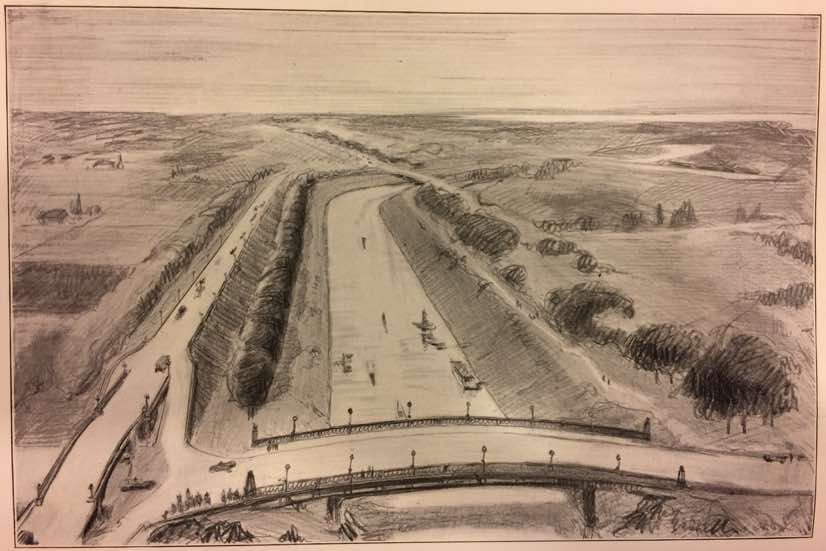

From the 1917 Plan of Evanston, with Bridge Street in the foreground and Lake Michigan in the distance.

In 1917, a few years after the channel was completed, Evanston planners envisioned parks along both sides of the new waterway. But development of this site was still years off.

In the 1940s, temporary housing was built on this spot and across the channel to house GIs returning from World War II. Housing was racially segregated: African-Americans on this side, White people on the other. The buildings were torn down in the 1950s and 1960s, leaving the area “a dilapidated eyesore.”

The Twiggs Family

Finally, in 1986, Twiggs Park was dedicated. The park was named for William H. Twiggs (1865-1960), a founding member of the Ebenezer AME Church and Emerson Street YMCA and first editor of a newspaper called The Afro-American Budget.

Community gardens

Twiggs Canal Gardens, one of four community gardens located in Evanston’s public parks, was founded in the 1970s by the Evanston Environmental Association. Every winter, plots for the next growing season are assigned by lottery. Gardeners grow a variety of vegetables, fruits, and flowers here, and in the summer, the gardens are abuzz with people and pollinators.

A recent addition to Evanston’s network of food-producing public gardens is located not far away, across McCormick Boulevard. Established in 2016 by Edible Evanston, Eggleston Food Forest is a diverse planting of perennial fruit-bearing trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants designed to mimic the natural balance of a forest by utilizing permaculture. Regular work-and-learn days are held there during the growing season.

Gardens like these add diversity to local landscapes, while growing and sharing food locally cuts transportation costs, carbon emissions, and waste.

Twiggs Canal Gardens © Claudia Grosz

Learn more about community gardening in Evanston

Opening up a view

Starting in 2017, the community has been working in the area around the deck, clearing weedy and invasive trees and shrubs that were blocking the view of the water and adding native plants.

Shrubs like hazelnut, dwarf honeysuckle, wild black currant, and a native rose are growing in on the slope. An afterschool group helped plant flowers and grasses along the top of the slope.

A haven for birds — and other wildlife

During warmer months, the Twiggs Park observation deck is a good place to catch sight of a belted kingfisher or great blue heron. Listen for the kingfisher's distinctive rattling call and the croak of the heron. More than 100 species of birds have been reported in this area.

Belted kingfisher in flight

It's not only birds you can spot from this overlook. You might see a turtle in the mud across the channel. If you're lucky, you might even glimpse one of the beavers who live here now or hear it splashing in the water. There have even been sightings of a family of minks.

Turtles are often seen sunning themselves on logs along the channel banks.

As this point part way back to the bridge, notice the dense green wall of shrubs behind the community gardens hiding the channel. These are mostly aggressive non-native plants that, over the years, have grown in along the channel banks and crowded out other, native plants.

Common buckthorn, shown in the photo above, was brought to this country in the 1800s as an ornamental plant, but now makes up more than 28% of the tree canopy in the Chicago region.

Removed from the environments in which they evolved and without natural controls, all of these plants reproduce freely, create shady thickets, crowd out other plants, and disrupt local ecosystems. Both buckthorn and garlic mustard have what are called allelopathic properties, meaning they inhibit growth of other, native plant species. Even deer don't like them. The effect is to greatly reduce plant and animal diversity.

Fortunately, many volunteers are helping with the ongoing work of invasive clearing along several sections of the channel.

Garlic mustard © Tony Atkin

If it's spring when you visit, you might see garlic mustard, which also flourishes in disturbed environments like this.

Buckthorn berries.

One of the most common invasives here is this Asian honeysuckle. It can be identified later in the season by its red berries.

Looking back

The Ladd Arboretum is one of Evanston’s largest open green spaces and an important resource for wildlife. But in 1960, when the arboretum was dedicated, the area where you are standing looked like this.

Growing conditions are still challenging here. The soil is mostly heavy clay from excavation of the channel, which has been compacted by years of heavy use. But thanks to dedicated volunteers and staff, the process of renewal and change has continued over the years since the arboretum was founded.

Ladd Arboretum 1960 © The Evanston Review

The 17-acre arboretum is divided by Bridge Street into two roughly equal sections. One is behind the Ecology Center parking lot, extending to Golf Road. The section ahead of you, shown in this historic photo, extends to Green Bay Road, and has long had a more naturalized character. Recent work to recreate native habitat so far has focused here.

Hard work pays off

If you visit in spring, it’s likely that woodland wildflowers will be making an appearance in the area near the steps leading down to a small dock you may have noticed as you passed the Ecology Center.

Transplanting wildflowers on steps returning from dock

There you might see mayapples, wood poppies, wild geranium, and even trillium. After trees leaf out and these areas become shady, most of these spring ephemerals die back.

Mayapple

Wood poppy

Mayapple & wild geranium

Trillium

Around the back of the Ecology Center, there's a rain garden where you may find Virginia bluebells. The garden is a demonstration of green infrastructure. Rainwater comes off the roof into the depression and plants help to absorb and hold the water as it soaks in.

Bluebells in rain garden a bit further along the path just past the Ecology Center

What does bird-friendly habitat look like?

Layered landscaping. Illustration by landscape designer Heidi Natura, whose firm Living Habitats has advised the North Shore Channel Habitat Project

As we clear invasive plants from the channel banks, we watch to see what desirable plants may be growing here then fill in with new plants native to this region. These three characteristics of bird-friendly landscaping guide the work:

Serviceberry © Vanessa Richins, Bugwood.org

Wild currant © Ryan Hodnett

Just beyond a big cottonwood tree, you may notice serviceberries and wild black currants.

Both of these produce fruits relished by catbirds, robins, and other birds.

A sunny patch for prairie plants

Butterfly milkweed

Little bluestem grass

Smooth blue aster © Dan Mullen

Rosinweed

Why focus on birds?

Millions of birds migrate through Evanston every year, and the arboretum is an important stopover place for resting and refueling. By planning with the needs of birds in mind, we are improving this area for other animals, insects, plants—and people.

In the words of Doug Tallamy, author of Bringing Nature Home, “If you have a diverse native bird population, it's a sign that the ecosystem as a whole is healthy."

The new plants are just beginning to grow in. It's going to take awhile—but we are planting for the future.

The North Shore Channel Habitat Project welcomes volunteers

Volunteers planted this area in October 2017.

A year later, it was alive with bees, butterflies, and birds.

Take time to listen

If it’s early April and you hear a tiny song in the tree tops, it may be a kinglet.

Golden-crowned kinglet © Gary Irwin

If you hear rustling leaves, it could be a hermit thrush, a well-camouflaged bird with a speckled breast.

Hermit thrush © Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren

From high in the trees, a flicker’s drumming and loud sharp calls may catch your attention.

Photo of Northern Flicker © Mike’s Birds

Later on in the season, catbirds like this one, as well as grackles and blue jays are often seen (and heard) in this area.

Catbird © Gary Helm

Birdwatchers have reported more than a hundred species of birds in this area to eBird, a list maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Maybe you’ll spot some of them while you’re here.

Look for these bird-friendly trees

Among the bird-friendly native plants in this area are pagoda dogwood and hawthorn. You might also notice a non-native dogwood called Cornelian cherry.

All of these plants produce fruits by early fall, which help to fuel migratory birds as they head south and support resident birds over the winter.

Pagoda dogwood

Cockspur hawthorn blossoms © Pinke

An area designed for butterflies and bees

Just beyond the Grady Bird Sanctuary, you'll find an area planned especially for butterflies and bees. A variety of flowering plants are sources of nectar and pollen; others are hosts for butterfly caterpillars. Dead branches and fallen logs also provide places for native bees to tunnel and lay their eggs.

Milkweed plants are essential for monarch butterfly larvae. One plot contains three kinds: orange butterfly milkweed, rosy pink swamp milkweed, and common milkweed.

Monarch caterpillar on common milkweed

More than monarchs

Coneflower with tiger swallowtail butterfly

It's not only monarch butterflies that make use of the plants in this area. You may see many other kinds of butterflies, bees, and other insects here during the summer months (like this tiger swallowtail feeding on a coneflower).

Cardinal flower

Hummingbirds also act as pollinators, and you may see them visiting red cardinal flowers as they migrate south in late summer and early fall.

Learn more from these sources

You can find out more about the butterflies and moths native to this area and the plants they depend on in this website developed by the National Wildlife Federation with entomologist Douglas Tallamy.

Match native plants with butterflies & moths.

Don’t forget to look up!

Oak trees are among the most valuable trees for birds

When you think of butterflies, trees may not come to mind, but they are at least as important for pollinators as flowers. Oak trees are used by 534 species of butterfly and moth larvae. Black cherries are used by 456 species. That also makes these trees important for birds. Caterpillars that emerge in springtime provide food for migrating and nesting birds—and by feeding on caterpillars, birds help to protect the trees from the hungry caterpillars. Oaks and cherries are both found in this area of the arboretum.

Some of the plant-pollinator connections are much more specialized. The spicebush swallowtail, for example, lays eggs only on sassafras or spicebush. We’ve planted clusters of spicebush shrubs in this area, too, in the hope of attracting these butterflies.

Birds and pollinators are threatened by loss of habitat as well as the widespread use of pesticides on conventional farms. The City of Evanston strictly limits use of pesticides on all public lands, and has signed on to the Mayor’s Monarch Pledge, which commits Evanston to creating habitat for monarch butterflies.